Olivia, Her Mother's Anguish

Despite health worries, Olivia Newton-John was determined to come to Australia for a family wedding. She and daughter Chloe, seven, flew in for the March wedding of the singer’s brother, Hugh, a doctor in Victoria. Much-loved Olivia, who is recovering after final chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer, felt Hugh’s wedding (it is his second marriage) should be a real family occasion and pulled out all stops to be part of the celebrations.

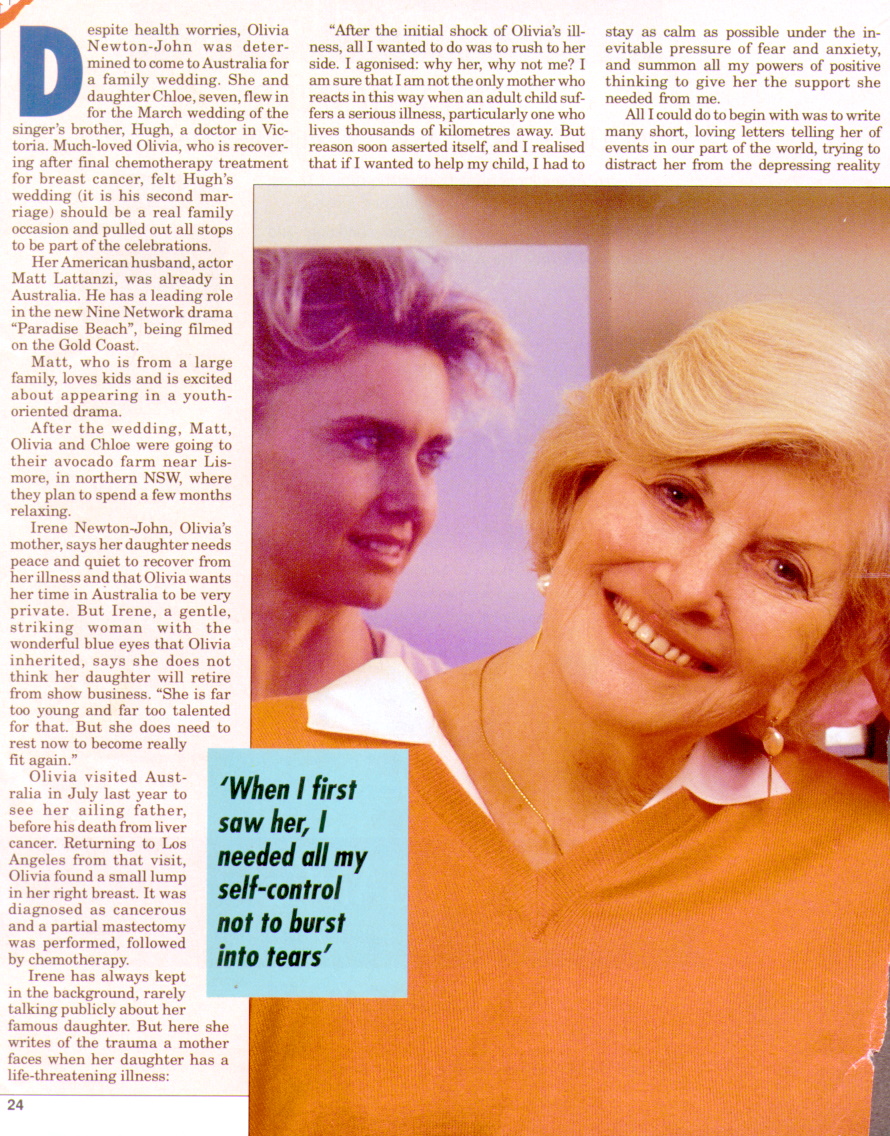

Her American husband, actor Matt Lattanzi, was already in Australia. He has a leading role in the new Nine Network drama “Paradise Beach”, being filmed in the Gold Coast. Matt, who is from a large family, loves kids and is excited about appearing in a youth-oriented drama. After the wedding, Matt, Olivia and Chloe were going to their avocado farm near Lismore, in northern NSW, where they plan to spend a few months relaxing. Irene Newton-John, Olivia’s mother, says her daughter needs peace and quiet to recover from her illness and that Olivia wants her time in Australia to be very private. But Irene, a gentle, striking woman with the wonderful blue eyes that Olivia inherited, says she does not think her daughter will retire from show business. “She is far too young and far too talented for that. But she does need to rest now to become really fit again.”

Olivia visited Australia in July last year to see her ailing father, before his death from liver cancer. Returning to Los Angeles from that visit, Olivia found a small lump in her right breast. It was diagnosed as cancerous and a partial mastectomy was performed, followed by chemotherapy. Irene has always kept in the background, rarely talking publicly about her famous daughter. But here she writes of the trauma a mother faces when a daughter has a life-threatening illness.

“After the initial shock of Olivia’s illness, all I wanted to do was to rush to her side. I agonised: why her, why not me? I am sure that I am not the only mother who reacts in this way when an adult child suffers a serious illness, particularly one who lives thousands of kilometres away. But reason soon asserted itself, and I realised that if I wanted to help my child, I had to stay as calm as possible under the inevitable pressure of fear and anxiety, and summon all my powers of positive thinking to give her the support she needed from me. All I could do to begin with was to write many short, loving letters telling her of events in our part of the world, trying to distract her from the depressing reality facing her.

She told me later that the caring and supportive letters from her many friends, and even from complete strangers, helped her enormously to keep her balance and to strengthen her resolve to beat the cancer. When, after a few months, I was able to visit my daughter and to spend some time with her, I needed all my reserves of self-control not to burst into tears when I first saw her. But somehow I managed it. As anyone who has been through similar experiences with a much-loved child will know, the tone of one’s voice and body language are most important in conveying the right message of quiet confidence and of complete faith in the effectiveness of the prescribed medical treatments, and in the certainty of a complete recovery. In the case of cancer, the treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation often seem to be making the patient worse, causing nausea and extreme tiredness. At such times it may be best to withdraw quietly. The sympathetic anxiety of a mother, however well concealed, may be felt as an added pressure. One has to sense when it is best to leave one’s child alone to gain rest. The presence of any other individual, however close, can be too much at a time when the sick person needs to re-examine his or her attitudes to life and death, and to re-evaluate their priorities and choices for the future.

There can be few mothers who have not lived through some painful and traumatic episodes during the course of their lives and survived all the stronger and probably a little wiser for the experience. Often our children are not aware that we, too, have been there and can empathise with their pain and confusion. Maybe we should tell them more about events in our own past, and of the battles we have had to fight by calling on our inner resources of courage and determination. In essence, what we are saying is: ‘If I could do it, so can you.’

It is often very hard not to interfere and to allow our children to find their own way out of a critical situation, even when in the light of experience we can see all too clearly where their decisions can lead. I have made it a general rule not to give advice unless it is asked for. I must admit, I have broken my own rule at times, but, on the whole, I believe that adult children must be allowed to find their own solutions in their own way, to learn from their mistakes and to grow and develop unaided. All we can offer them is our unconditional love and a safe refuge when needed.” By IRENE NEWTON-JOHN